When I ask my clients where they found the biggest benefit in my How to Use a Calendar program, they often reply:

“Scheduling for 30, 60, or 90 minutes.”

It’s tempting to block off a massive chunk of time for a big project. Whether that massive chunk of time is a an afternoon, a day, or a series of days – doing so subtly encourages procrastination in two ways;

- It doesn’t specifically define the desired outcome

- The extended duration of time allows you to constantly say, “I’ve got plenty of time to figure it out.”

Overcoming both of these requires peeling apart the project into smaller, more discreet, incremental tasks. Then estimating the time to accomplish each of those specific tasks. Finally, scheduling those tasks with their corresponding estimated duration on your calendar.

This has three subtle benefits:

- Timeboxing each task mildly increases the sense of urgency to complete it, for this is the only time available for this part of the process (er, project).

- Increasing the number of completed tasks makes it easy to see progress and build momentum toward a larger goal.

- Discreet task level scheduling makes it easier to confidently communicate expectations of progress to yourself and your collaborators (at whatever granularity is appropriate).

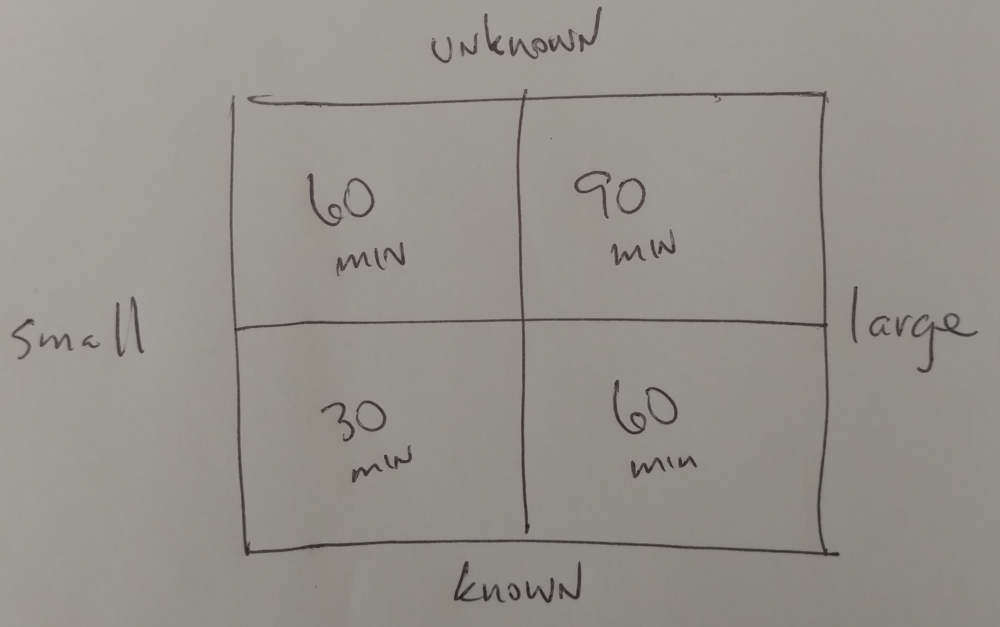

I encourage my clients to use the following estimation framework I talk about The Power of When:

- 30 minutes for a small, known* task.

- 60 minutes for a small, unknown task.

- 60 minutes for a large, known* task.

- 90 minutes for a large, unknown task.

- Tasks taking longer than 90 minutes should be broken up into more smaller, more specific tasks.

*known = something you’ve done before and can confidently complete within minutes

Why 30, 60, and 90 minutes?

- Nothing takes less than 30 minutes.

Once you factor time for preparing do do the work (including switching mental contexts), reviewing the work to ensure it has in-fact created the desired outcome, and properly closing out the work – nothing takes less than 30 minutes. Not even replying to that important email or phone call. This is before factoring in any disruption or interruption. - If you can’t achieve the outcome in 60 minutes you need to step away.

Sixty minutes is a long time to be intensely working. In endurance running it’s here at 60 minutes where you need to start considering additional food & water to counter act the physical and mental fatigue. The same goes for intense creative work. Fifty minutes into a task, you know if you’ll reach the intended outcome within the next ten minutes or not. Either way, stop after those ten minutes, step away from the work environment, and get something to eat and drink, take a walk around the block. I’d be willing to bet, when you return you’ll have a new perspective – if not a breakthrough. - After 90 minutes you’re fried.

Maybe you figured, this tasks is just a little bit bigger, a little bit unknown, but totally do-able with a little push past the 60 minute mark. Ninety minutes would get you to a more substantial milestone and more resilient stopping point. Fantastic. Go for it. Know that at the end of it, you’ll be completely fried, totally mentally drained. The break we talked about at the 60 minute mark? Yeah, it’ll need to be longer and even more re-energizing than before. Especially if you’re expecting to do it again when you return. The best place for intense 90 minute tasks is very first thing in the morning and the very first thing after lunch.

Now, what if you reach the outcome before the estimated time is up?

- Review it thoroughly to confirm it is in fact completed. You might be surprised to find one or two more small, quick, easy things that could make it that much better.

- Pat yourself on the back for beating your estimation and take a break.

If you’re interested, I wrote this post in two 60 minute sessions with an hour lunch in between.