“The better you understand context, the more likely you will see how easily you can be missing out on it.”

Tyler Cowen, “Context is that which is scarce”

Magnus Neilsson‘s “Nordic Cookbook” is one of my favorite books, primarily for how it opens:

“If you follow the recipes to the dot as printed in the book, sometimes it’s not going to work anyhow…The way ingredients behave in one part of the world might not be the same as how they behave where you are, for natural reasons…Are you getting discouraged? Well don’t…Recipes are there to give you a base to start from, inspiration…and also to explain the technical base on which you can then build….You will have to use common sense.”

Tyler Kord’s “A Super Upsetting Book about Sandwiches” opens similarly,

“Being able to follow a recipe is like being able to read music, and you should feel free to make it your own a little, because nobody will mind if you like your broccoli a little more cooked than I do….”

And from Belinda Ellis’s Biscuits,

“A recipe can’t tell you exactly how much liquid to add because of the fat content of the milk, the amount of protein in the flour, even the weather can affect the moistness of the dough.”

At the beginning of summer, I walked into the neighborhood library and the librarian asked me why I had the recipe for bread on my shirt.

“I’ve committed to entering a loaf of bread into the Minnesota State Fair.”

Yes in fact, a few weeks earlier, I selected a recipe out of Ken Forkish’s Flour Water Salt Yeast to master and have been baking 2 loaves of bread every week since.

No, I haven’t been happy with any of them. Thank you for asking.

In an attempt to get happier, I switched yeast (somewhat better), then I switched flour (much worse), then I introduced a kitchen mixer (much much worse), then I switched flour again (somewhat better).

As much as Forkish’s recipe is far more sophisticated than my t-shirt – or the title of his own book – turns out it’s also a long way from the level of sophistication required for success with this flour, this yeast, in this oven, in my kitchen, in summer, at this altitude.

At beer club, if you’ve a question about anything in your most recent batch the first response you’ll get from the more experience members, “Did you bring your notes?”

So, like anyone screwing around doing science, I’m taking notes. I’m documenting what seems to work in each batch and documenting how I diverge, inadvertently or otherwise, from what the recipes states.

In the end, if I’m successful, I’ll have this one bread recipe adapted/developed, and if written out comprehensively for someone else (even future me), it will likely be >4 pages (it’s already 2 pages). Four pages is quite a bit longer than four words.

This massive discrepancy in length is obvious to anyone having developed a recipe – especially one targeting commercial food equipment at scale. Or anyone having built and refined anything from zero. There are a number of non-obvious details that are only a concern if the goal is: make it repeatable.

The Ninety-Ninety Rule aims to remind us there are always non-obvious details, context, and decisions that are only encountered once we’re in the middle of an effort.

The Coastline Paradox reminds us of a similar phenomenon, if you were to carefully walk the entirety of any coastline, the distance walked will be longer than any measurement of the coastline. Which is to say, the complexity of a situation is far higher when you’re in the middle of it than when you’re an observer.

Years ago, Merlin Mann recorded (by my assessment) a classic NSFW rant entitled, Make Believe Help. In it, he drags all the internet publications trading in reframing common sense as the latest life hack. For contrast, Merlin evokes an Old Butcher – an expert in the small details gained through hundreds, thousands, of repetitions.

These reps matter.

Making the same cut over and over. Each time doing it wrong in a different way, in a different spot. Then again. And again. And again.

An active practice.

Reps are only thing that will develop skills beyond what fits on a t-shirt.

Everything that’s not real world reps lacks necessary context, the necessary details, the appreciation for how all the factors fit into place. All the factors, not just the obvious ones.

Accelerating skill development requires creating an environment for the reps, for the practice, including a post-rep assessment;

- Was the target achieved?

- What went well?

- What didn’t?

- What was different this time?

- What do we want to deliberately focus on in the next rep?

Any individual instance matters less than the accumulation of all the instances. There will always be another instance.

All of this is well within the Double-Loop model of learning, which is self-aware:

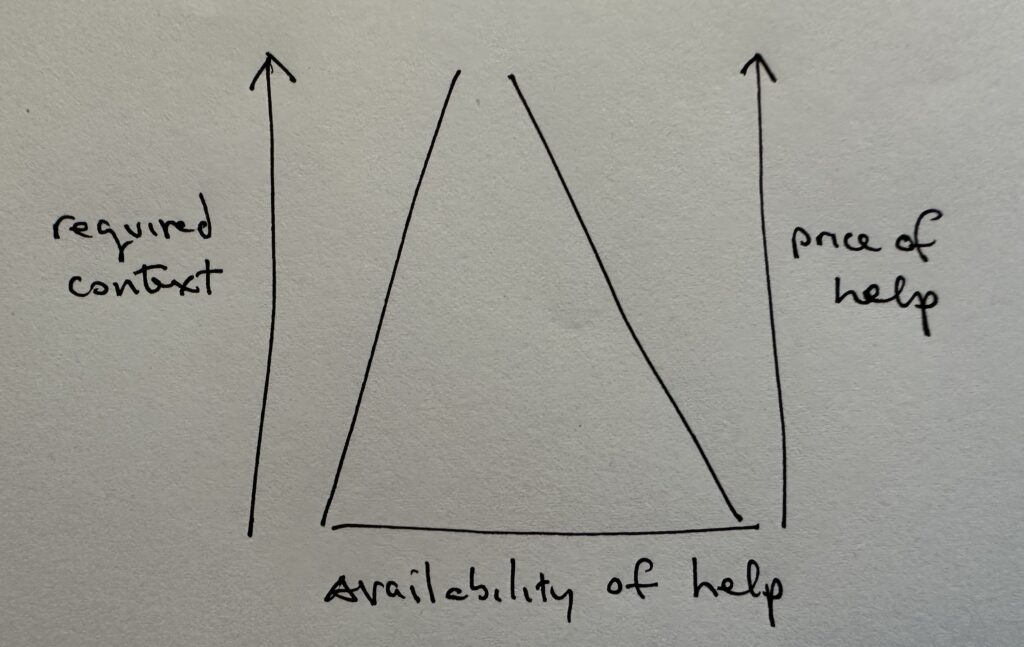

Of course, this is why we have coaches, advisors, structured classes, and multi-year specialized educational programs – all to accelerate the acquisition of greater context for a price. To help us get better at defining the problem accurately.

In my work with startups, I’m continually listening for hints of such an environment an real world reps – whether dogfooding or helping a customer solve a problem today. This is usually evident in if, and how casually, they talk about details and problems non-obvious to an external observer. A surprisingly small number have. Some resist even the mere suggestion. I get it. Real world reps can smell like low-value work that doesn’t scale, especially when your end goal is to abstract and automate away the pesky details. But here is where real competitive advantages lay, not to mention early revenue.

Admittedly, as this story of the Vienna Beef company reminds us, we can be successful for a very long time without fully understanding our own non-obvious details.

No, at this moment, I have no evidence this particular recipe would even do well in the Minnesota State Fair. Yet, I’ve committed to this recipe because it looked interesting, delicious, and slightly challenging. All of which could be part of my problem.

How many more reps can I get in before the drop off date?

“…The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds;…who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls…”

– Theodore Roosevelt, “The Man in the Arena“.